Kimberly Ellen Hall & Justin Hardison

Justin Hardison: I feel like you’ve always been collecting knick-knacks, as long as I’ve known you, and you always liked the stories behind them, so I’m not surprised that you were drawn to the residency at RAIR. Is this what drew you to it?

Kimberly Ellen Hall: Yes. I like to dig in the trash. I like to collect stuff that’s free. It becomes a part of what I make. It’s irresistible. When I applied for this residency, I thought, “This is going to be the best thing that’s ever happened to me in my whole life,” not about art, just about that somebody is going to let me roam freely in a bunch of stuff that everybody’s thrown away. It’s a bit weird to say it that way, but it’s true.

JH: Once you got out there, were you surprised by what you found?

KH: Well, I have to say there’s a lot of sheet rock in that recycling yard! That was not interesting to me in the slightest. There was a lot more stuff that I was not interested than I had thought there would be.

JH: What kind of things did you find? Was there anything you wish you had hung onto that you didn’t?

KH: Well, a lot of the things that I drew. I mean, I wished I could have taken everything home that I drew, but even though I now have a house, it’s just not big enough for going to RAIR every day. Yes. Yes. I wish I took everything home. I want a warehouse, and I want to fill it up with all the things at RAIR.

JH: When you applied for the residency, I guess you have to put forth some sort of proposal, so you had some sense of what you were going to do, or did you have a concept behind your project going in?

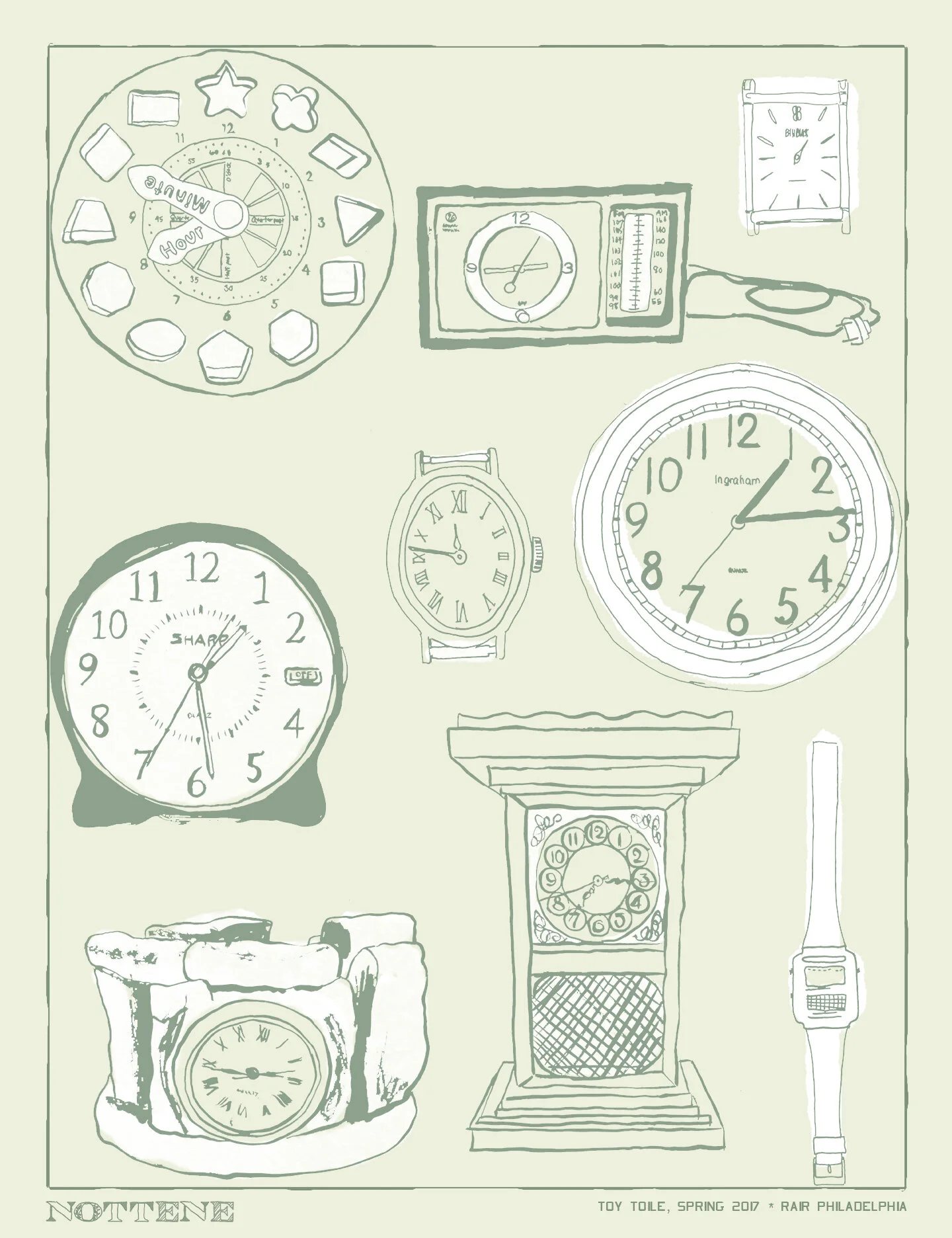

KH: I mean, I tried to keep it pretty open, but I knew that I wanted to draw things from the trash. I knew I wanted to find a way to take the things that people threw away from their houses and put them back in people’s houses. That was sort of my driving idea.

JH: Is that why you felt like the objects would be good wallpaper or a good subject for wallpaper?

KH: I didn’t know what things I would find exactly. You know, I hoped it would be like the big dream thrift store in the sky, but I just thought there was something so nice about making it into wallpaper that people would buy, and then they would take representations of all that trash and put it in their house. As if it was special and important, and I like flipping it around like that and maybe feeling maybe like I’m tricking people a little bit into loving trash.

JH: Into loving trash?

KH: Yeah, because I think so many people, when you see ... I mean, it’s kind of gross out there. You know, I was nervous the first few times I went out in the yard. You don’t know what’s in there. You don’t want to get hurt, or step on things, or touch something yucky. You know?

JH: Did you feel weird rummaging around through people’s garbage? For their belongings?

KH: No.

JH: But I imagine like it was pretty personal stuff, like people think that when you throw something away, you’re getting rid of it, never to be seen again. At least I do.

KH: I think that I approach it with a real love and a real care. I really feel the connection between the person whose stuff I find and how I would want my own stuff to be treated, and so I feel a real protective instinct. I feel very mother-ish about it. You know? I feel very much that it’s been put into my care, and it’s special and important, and I want to take good care of it. I would never want to treat it like trash. I guess that’s sort of how I feel. I’m going into the trash and collecting all these things that have been left behind ... you know, all of the little runts that have been left behind. I’m going to collect them up and take good care of them.

JH: You ended up with a lot of groups of objects from a specific person or persons. Was it pretty easy to do detective work and figure out?

KH: It was surprisingly easy.. I mean, sometimes there was a few things that are questionable, like that didn’t seem to belong, but most of the time it was really clear. Most of the time you could find something that talked about who the person was, or the couple... It could be anything, but personal things with names on them. That stuff I didn’t feel the need to take so much, but it would help me sort of draw a circle around the things that I found, so that I could sort of tell what belonged to them.

JH: I think it’s fun to make up or come up with an idea of what people are like based on their trash… I imagine what would somebody think of me based on a bunch of my belongings in the garbage? What would they surmise from my stuff?

KH: I thought about that a lot. I thought about how we make these assumptions based on these groups of objects, because I couldn’t draw everything from every person. There would be a whole truck full of somebody’s stuff so I couldn’t draw everything, so I also had to select what to draw. Then when I was making the wallpaper, I had to narrow it down more about what would fit on a panel. You know, it’s edited. I had to make decisions. It’s not raw data anymore. I shaped what the story of this person is. One of the things I realized when I was writing about it a bit, was that I wanted to talk about how these collections of objects are no longer meant to be representations of a particular person, but they’re meant to give us an idea, to think about what the things we throw away tell about ourselves. At this point it’s not a realistic representation of any of those people anymore, because I’ve manipulated it. I’ve picked the things that I show, and it’s more meant to be a story.

JH: Oh right, that’s true.

KH: You know, it’s meant to be a narrative to help us all think about when you take a bunch of stuff to the thrift store, or you throw a bunch of stuff in the trash, or you call the 1-800-Got Junk truck, and you put that stuff theoretically in a hole in the ground, what does that mean? Why? Then hopefully when you’re going to the store and you’re buying stuff, you’ll think about that too of like, “Why am I buying this stuff? What does it say about me? Is that really what I want to do?”

JH: I guess when I was out there I just assumed that the belongings were owned by somebody that was no longer alive.

KH: I don’t think they all are. I think there’s evictions or people who’ve moved away and left stuff in a storage unit. They’re not necessarily passed away. I mean, they’re gone. They’ve left that stuff behind.

JH: I just always imagined their life being reduced down to the bag of garbage and chucked out. That’s it.

KH: Do you think about that for you? Does it make you think about mortality?

JH: Kind of. Yeah. It did make me think about mortality. Yeah. Like, “Oh. There you go. A bag of crap, leftover stuff.”

KH: That’s all that’s left.

JH: Yup. Checked out, and somebody’s digging through it, making artwork out of it.

KH: I mean, I think it’s kind of nice to think that somebody’s digging through it and making artwork out of it after you’re gone, because at least you’re continued in some way, even if it’s about more than just you.

JH: Yeah. I guess so.

KH: So I want to ask you how it feels to be on the receiving end of all that stuff? I mean never mind that I’m a junk collector. I think you’re a junk collector too, to be honest. But I wonder how it was for you to print all these things and be presented with these sort of edited stories of people? How did you find what the people were like or how did they feel?

JH: I don’t know, it’s hard because I almost wish I didn’t know so much backstory on some of the objects, because I felt like it kind of skewed my view a little bit. For some reason, maybe I’m just morbid, but I just always imagine those people as deceased and I felt a little creepy. Almost like I felt like I was peeking in on their private lives. I mean I don’t really know who they are, but I felt like this was stuff they’d discarded and I felt weird looking at it all.

KH: It would be interesting I think to see if people ask us about that, when we launch them in March, when we’re at the trade show. Do you think people will ask stuff like that?

JH: I’m not sure. They say privacy doesn’t exist anymore any right? So, not even in your trash.

KH: What did you think about going into the yard? I know you only visited a little bit but...

JH: I guess I was just surprised by the sheer volumes of trash. There are some days where it’s just truck after truck, just lined up, just dumping stuff off. It’s just crazy to think it happens every day. There’s lulls but I was just surprised by the amount of stuff, but at the same time it was nice because they’re recycling a lot of it. So it’s nice to see them being reused.

KH: Yeah, they try and recycle everything they can. Otherwise they have to pay to landfill it, so you know it’s their goal is to recycle every scrap that they can.

KH: What’d you think about the smells?

JH: I don’t know. It definitely had a very distinct smell. I thought it was the drywall, I can almost still smell it actually.

KH: Yeah. Some days it would smell different than another days. But there was always a similarity, like underlying. Every now and then you’d like poke into a bag and you’d get like a horrific smell.

JH: I like watching the trucks dump everything and you know there’s glass coffee tables and TVs and stuff… I would imagine. Okay, well to switch gears, I was just thinking it seems like a lot of people are getting rid of stuff. You know, they’re going minimal and getting rid of clutter, and trying to free themselves of having to take care of so many objects, and maybe reduce the stress of the time that it takes to take care of those things, whatever the reason is. Maybe it’s just trendy, maybe they want to look like Dwell Magazine, but I don’t know. You’re almost the opposite of that. Do you think that something valuable is being lost by people having less?

KH: I think about that too sometimes. I think that it’s not really about the number of objects that you have.

First of all, I feel the same way as those minimalists in that I don’t think it’s worthwhile going out and buying new things all the time. The thing that I think is important is holding onto the things you have for a long time. The things that I have in my own life, I like to keep them for a long time, because I think it’s that element of time going by that makes them special or important. I might have a lot of stuff and a lot of knick-knacks, and I like to go to the thrift store and spend $6 and come home with a bag of treasures, but there’s something about the amount of time going by and the length of time things have existed that make them feel special or important to me. So, yeah, I would align myself with those minimalists, in the sense that I don’t want to go out and buy a bunch of new stuff. I don’t want stuff that’s new very often. I mean, sometimes, right? Sometimes we need new stuff.

JH: Yeah. That’s true.

KH: Sometimes you just need new underwear. It’s not that you can’t never have new stuff, but if we’re talking about decorative objects and the beautiful things in your home or your life, the things that are decorative, I think you should have things for a long time. That’s why I don’t want to make removable wallpaper. I want to make wallpaper that’s going to stick on the wall for a long time, and maybe that’s not very popular. I don’t know.

JH: Yeah. Maybe. When you were out there, did you ever feel like you wish you were a sculptor or some other kind of artist?

KH: Well, I definitely wanted to rescue all those things out of the trash, and then I want to find homes for all those things. You know, I want to give them to people or sell them to people. I don’t know any realistic thing I can do, but you know, I want to go there every weekend, and I want to save all the treasures, and I want to put them in a big warehouse, and I want to let people come and get them. I don’t know. I don’t know the commercial way to approach that, but I want to rescue them all and find homes for them all. I want to talk to every person that comes in, and I want to show them special things, and I want to say, “Oh. You should look at this. This would be just right for you. I see your green bag. I’ve got these green things that you would love those.” I want to be the little, old lady that knows all her customers and says, “Oh. I’ve got the newest thing just for you.” I want them to be really special.

Kimberly Ellen Hall & Justin Hardison are a husband and wife team who run a print and pattern studio in Philadelphia. Our studio is called Nottene, pronounced [nuh-ten-uh]. We produce our own collection of hand-drawn and screen printed wallpaper. Our studio work comes from a practice of storytelling through drawing, and we like to push the boundaries of what is possible in screen printing to see how much of the details and pleasant imperfections can be brought out during the process. Our newest collection, launching next month at Architecture Digest Design Show, that came about through the artist residency that Kim did at RAIR is inspired by the lives we found sifting through the things people throw away. It is designed to reflect early wallpapers, called domino papers, that were small repeatable tiles hand printed on paper and used for decoration on a variety of surfaces.